The Spirit of Winemakers

Finding Religion from the Vineyard to the Bottle

The Spirit of Winemakers explores the colorful spiritual lives of some of the most famous and interesting winemakers in the world. While few winemakers today pray to Bacchus or make their wine in monastic cellars, this book reveals that deeply held and sometimes peculiar spiritual beliefs still motivate many in the wine industry. From Jewish mysticism and Daoist philosophy to Zen meditation and Hindu-inspired crystals, there is so much more that goes into wine than just grapes. Grounded in over one hundred interviews across three continents, this study will open your eyes to the spirituality that shaped the wines you drink and invite you into the inner lives of the people who make the wines you love.

Click here to Purchase a Copy through Amazon

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: God’s Own Winemakers

Chapter 2: Drink Here, Now: Zen and the Art of Winemaking in the West

Chapter 3: Biodynamicism

Chapter 4: Spiritual (but not religious) Winemakers

Chapter 5: Wu-Wei Winemakers

From the Introduction:

Ursula was a wine grower in the McLaren Vale, South Australia when she had a vision that she was supposed to travel to the Himalayas. She left her vineyard in the hands of capable family members and traveled to find wisdom in the ancient mountains that top the world. When she returned, she personally eschewed drinking wine in exchange for purely spiritual sustenance, but she continued to make the divine juice for others. However, she was changed. She began to walk through the rows of vines touching each vine and telling it that she loved it. And she genuinely loved. Each vine. Each berry. Each leaf. She no longer merely cared for the vines, she communed with them. She also healed them (and people, by the way), even from a distance. They responded to this love by producing great fruit that was converted into ethereal wine.

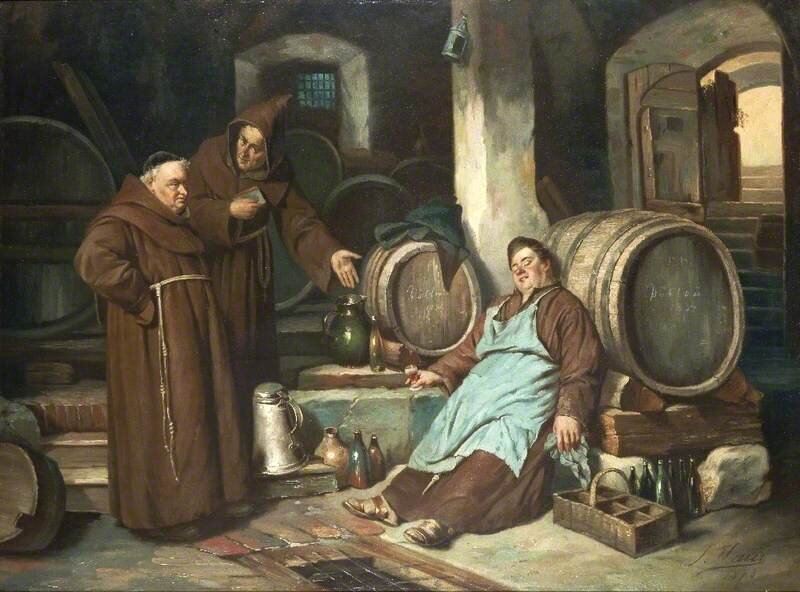

She’s retired now but she still recognizes that in the world of wine, she probably marks the far edge of the fringe. She is right in one sense: modern winemakers are not known for being a spiritual bunch. Long gone are the days when winemakers called upon Dionysius to make fermentations happen; furthermore, it has been five hundred years since most wine was made by monks in monasteries. Rather, the average winemaker today is trained to be an oenological scientist working in sterile laboratories surrounded by the latest vinification technology. At times it seems that the only romance left in parts of the wine world happens with the grafting of a new clone, if the sex life of grapes can be seen as romantic. Wine journals today are filled with pithy verses about reverse osmosis and tantalizing exposés about the ROI and M&A of neighbor’s wineries. Glamorous wine events abound where winemakers pretend that they are comfortable in suits, conversing about ratings and auction values as if their wines were stocks and bonds rather than agricultural products. It is no wonder Ursula feels out of place in the modern world of wine. Yet, she really shouldn’t.

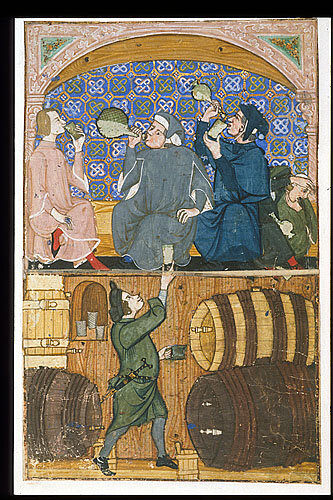

Under the shiny veneer of the modern wine industry, the people responsible for the wine have changed less than they let on. They may not pray to Dionysius anymore at vintage but there are winemakers who place written verses containing positive affirmations on their fermentation tanks to encourage their grapes or pray over every fermentation vat. Visit a winery during vintage and you may be able to hear, just above the coolant system, Gregorian monastic chant or for at least one notable person, a single musical note played live that is supposed to “energize” the wine. They will laugh if you ask them about animism (the idea that everything has a soul), but I lost track of the number of winemakers who told me they talk to their wines—and think they respond. Winemakers “heal” their wines by passing them through quartz crystals or aging them in pyramid-shaped vessels. I heard winemaker tales of sleeping on their cellar floor during vintage and waking every few hours, revealing a discipline and dedication that would make Abbots envious in years past. There is even an International Federation of Bacchanal Brotherhoods, a contemporary wine society that consciously links itself back to the piety (and the feudal system) of a millennium ago, that performs elaborate hidden rituals to initiate brothers (and now sisters) into a stream of winemaking traditions that dips far back into the recesses of history. In fact, when one starts scratching the surface, spirituality seems to sneak into wine almost as much as additives; but like additives, everyone likes to pretend it isn’t happening. Ursula just thinks she is alone.

This book is based on interviews with nearly a hundred winemakers around the world, who generally would rather talk for hours about the benefits or harm of extended maceration rather than talk for a few minutes about their personal spiritual beliefs. Undoubtedly, there are many winemakers who are utterly deaf to the spiritual side of life. Some of them still make great tasting wine and are incredibly successful at their trade. This book is not about them. It is about those for whom wine is more than just a job, even a job they really love; it is a calling. They are without question wine devotees but they are more than that: they have dedicated their life and placed their livelihood in the hands of wine. It is not merely a hobby or even an obsession but closer to a vocation—something they would do even if they wouldn’t get paid. While some were born into wine families, most of them experienced at some point an event that so transformed them that they could no longer continue their previous life’s trajectory. These are the spiritual winemakers.

Having asked them about their spiritual life, it is hard to tell if the world of wine has attracted some spiritual people or that if you make enough wine, you eventually end up seeking spirituality. Probably, it is a bit of both, with certain vintages driving people to their knees more than others. On the surface, the spiritual winemakers share very little in common. Some are Christians, some are Buddhists, some are atheists, and some just shrug their shoulders when I ask them their religious identity. They differ in age, sex, place, and personality. Yet they all hold that there is something bigger going on in the wine business than just hocking spiked grape juice. They all hold that some of the most interesting parts of wine are unmeasurable and unseen. And they share a belief that wine is part of their spiritual journey, not opposed to it.

In chapter one, we meet those who think God is behind all great wines and so they develop a theology of wine where they serve God through their oenological vocation. In chapter two, we turn to the east and look at winemakers who have been shaped by the religions of India, Hinduism and Buddhism. Chapter three is dedicated to biodynamic winemakers, for whom wine has a place in the overall cosmos that is critical for its proper cultivation. In chapter four, we turn to the “spiritual but not religious” crowd of winemakers, who eschew formal religious connections as they turn to the non-material parts of wine. Finally, in chapter five, the focus is on winemakers who do not necessarily fit into a traditional theology or system but have a strong sense that there is a natural harmony within wine that reveals itself when the human tendency for control is given up. I call these winemakers “Wu-Wei Winemakers” after the Daoist notion of active passivity in the pursuit of the Dao.

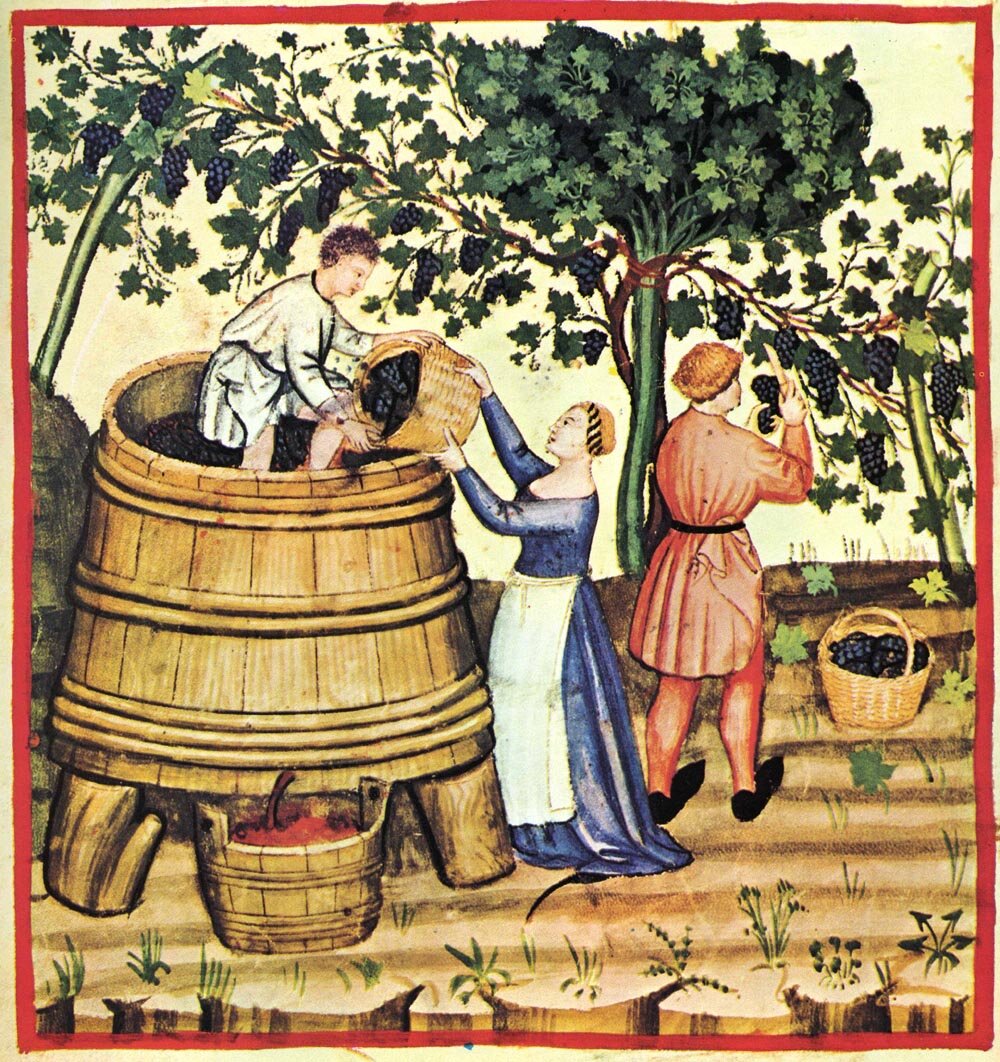

Nearly all the wine producers profiled in this section shun the term “winemaker.” They note that winemaker is only a new world term; there is not word for winemaker in French, Italian, or Spanish. Like a thoroughbred trainer coaxing the highest performance out of nature or the midwife who guides the natural process, these winemakers see themselves as shepherding the grapes as they reach for the highest expression of what they already are. Vigneron, a word that awkwardly translates into something like wine grower, is perhaps better but still alters the spirit of their task. If it hadn’t become so cliché, perhaps something like wine whisperer would be best. Whatever the name, these winemakers have a different relationship to the fruit of the vine than non-spiritual winemakers. The making of wine is not just a passion but it enters into the spiritual realm of life. The soul of wine has lodged in their hearts and souls. As a result, the wines of spiritual winemakers have become oenological expression of love.

Most winemakers may just want to make some “kick-ass booze” as one Australian told me. Spiritual winemakers are not opposed to that goal either. However, they want something more from their relationship to wine. In ancient Greece, they would read the leftover lees as clues to Fortune; they were a conduit to the spiritual dimension. Spiritual winemakers want the same: for wine to become a conduit to the fourth dimension: spirit. And so when they press their grapes or rack their barrels or fill their bottles, they offer not just their brawn and brains to the process but their heart and their soul. The resultant bottle reflects not just their winemaking technique but also their love, which they long to share with others.

Ursula, the Australian winemaker who caresses each one of her vines, undoubtedly loves her vineyard. Each vine. Each leaf. Each berry. Anyone could tell who watched her weekly vine-caressing ritual. Yet she also found something more through her wine, through her love. Perhaps we should call it oenological illumination. So, grab a glass of wine as you read, for the goal of this book is to convey the transformative power of bottled love with you, the reader.

“The Spirit of Wine has now found its voice in song! Listen to My Beloved, Pinot Noir by Jason and Debbie Manville, performed by Sip & Chew”